In 1980, when he was barely 28, a Spaniard, Andrew Olea (born in Granada in 1952), had just completed his degree in Philosophy and Letters when he left his native Andalucia and flew to Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. He had accepted a position with an NGO—Strathmore Educational Trust (an Opus Dei-related initiative dedicated to the education of young people). Olea was embarking on an adventure to which he is still fully committed, 30 years later.

In 2003 he organized The Eastlands, a project that offers professional training to young people in poor neighborhoods of east Nairobi. Most of those who make use of its services have begun small businesses in the “informal sector,” the Kenyan term for street vendors who seek to improve their living conditions by offering housewares for sale.

About three-fourths of jobs available in Kenya are in this sector; earnings range from $70 to $420 per month. The vendors, who lack a college education and thus are unable to get more productive jobs, have chosen to earn a living in these small businesses. “But a simple course in salesmanship and marketing, which our NGO provides, is sufficient for them to serve as outlets where companies can sell their wares directly to consumers.” The Eastlands has helped many young people acquire skills at different levels of accounting, management, computing, and marketing, according to their interests and needs. What began as a small seed has grown into a sturdy tree that has helped nearly 4,000 young workers.

A Sports Program

Along with instruction, The Eastlands also has sports facilities. To improve them, the NGO recently signed an agreement with the Athletic Foundation of Madrid, whose objective is to provide sports fields and to promote interest in soccer as a way of helping young people in poor neighborhoods to improve themselves and to stimulate their educational incentives.

After more than 50 years of social work in Kenya, the Strathmore Educational Trust has increased its involvement in Nairobi with this new project. Olea came to Barcelona recently to discuss his plans to add a technological center for professional formation that would help alleviate the country’s poor job outlook by enabling experienced young workers to move on into industry.

This initiative will include training in industrial maintenance and business computation, schooling for fathers, and athletic training. “Besides the NGO, we want to extend our capability to respond to the present needs of the country, which is clearly in a developmental stage of industrialization and needs well-trained and experienced workers. To provide them is our goal.” In this way, it is a model of dual formation, for it can help the formal sector as well as the informal.

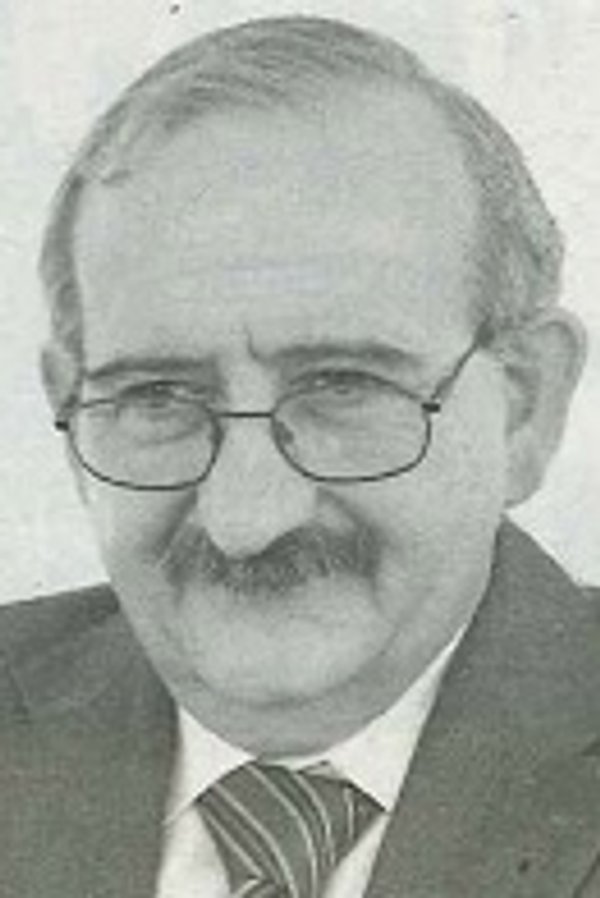

IInterview with Andrew Olea, Executive Director of The Eastlands Project

Is professional training the best investment for Africa today?

I sincerely believe it is. A country’s wealth is its people. There are many examples of countries with limited natural resources that are among the most developed in the world. The Netherlands, Switzerland, and Japan come to mind.

Where is the wealth of those countries? The people, who have been trained to create more wealth. Germany is another example of a well-trained people who generate more development. Therefore, we of The Eastlands Technological College are thinking about following the German model of education, where students spend 70 percent of their time on the job.

What has been your experience in Africa? What so attracts developers to those countries?

For me, the main attraction was the people. They are simple, open, enterprising, hard-working, and tenacious. Of course, there are many problems there, but they do not discourage the people from working. Then there are other values one finds in Africa, notably the family, solidarity, and generosity. Therein lies the reason to hope that these countries have a bright future. Naturally, nobody is perfect. So on the other side, Christian virtues have not yet had time to become firmly implanted in African societies. Christianity arrived scarcely a century ago. And then there are unfavorable comparisons with the West, where in many countries it has taken centuries and centuries to achieve many things that are yet to reach Africa. In Kenya, for example, many families still depend for their living on the father’s or the grandfather’s daily catch of fish.

From a more personal point of view, how has St. Josemaría’s emphasis on the call to sanctity through one’s work caught on in such a lively and joyful culture?

Christianity, and especially Catholicism, is a joyful religion that finds God in nature, and everywhere. St. Josemaría’s spirit is one of joy on seeing God behind everything that is done or happens all around us. With his spirit, one lives with a heart that is forever young. One takes life’s challenges as a person would who sees himself as a son of God, and therefore as expecting the best from his Father, even if sometimes he doesn’t understand what happens. … God is my Father and he loves me. All this fits very well in a young society that is full of hope and with eagerness to work to find a place in a world that seems ignorant of God and man.